President Obama’s deployment of 100 US combat forces to Uganda and surrounding areas has shocked many as highly unusual and even downright bizarre. But while ground troops in Africa are a comparatively rare occurrence, the decision follows a very familiar path of dominant US foreign policy.

Obama’s justification for the war-by-presidential-decree was twofold. First, Obama injected the ubiquitous humanitarian rationale, accurately noting that the Ugandan-based militant group the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) “has murdered, raped, and kidnapped tens of thousands of men, women, and children in central Africa.” The use of this rationale is as common in US military interventions as it is fraudulent, given US administration of, complicity in, and disregard for comparable atrocities around the world.

Obama’s justification for the war-by-presidential-decree was twofold. First, Obama injected the ubiquitous humanitarian rationale, accurately noting that the Ugandan-based militant group the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) “has murdered, raped, and kidnapped tens of thousands of men, women, and children in central Africa.” The use of this rationale is as common in US military interventions as it is fraudulent, given US administration of, complicity in, and disregard for comparable atrocities around the world.

The other of Obama’s justifications asserted a “national security interest” in fighting the LRA. Using the normal definition of the phrase, this is not just implausible; it’s far-fetched. The LRA pose no direct threat to the US, and indeed are at their weakest point in 15 years, with only 200 to 400 fighters at current, down from 3,000 armed troops and 2,000 people in support roles in 2003.

If the “official” state definition of the phrase is used, however, the assertion is probably accurate. In official foreign policy doctrine, “national security interest” often means the interest of corrupt dictatorships, albeit ones that are obedient to US demands.

For years, the US has lent economic and military support to the Ugandan government, now headed by the regime of President Yoweri Museveni, reelected earlier this year in a vote that was widely disputed by international observers. And since the US war in Somalia has intensified, relying on obedient state thugs in neighboring countries is ever more important.

Ostensibly aimed at the rag-tag al Shabaab militant group, the US has expanded its drone war in Somalia. It has also doubled down on a proxy war in which one group of militants gets US support, while the other – indistinguishable from the first – is targeted. Meanwhile, the CIA and Joint Special Operations Command are running what amounts to a kill/capture program in the country.

In this context, US support for the Ugandan regime has increased as a bribe to fight this latest US war. In June, the Pentagon sent part of a $45 million package in military equipment to Uganda. The aid included four small drones, body armor and night-vision and communications gear and is in part being used against al-Shabab. The request for aid to Uganda in FY 2012 is set at over $527 million.

Capturing LRA leader Joseph Kony remains the highest priority for Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni. As the Washington Post reported, “military advisers in Uganda could be payback for U.S.-funded Ugandan troops in Somalia.” Keeping Museveni – a dictator who has been deemed “president-for-life” – content and swimming in weapons and money is what will keep him willing to fight a dangerous and brutal proxy war for the US.

The approach will be familiar to anyone knowledgeable of the history of US foreign policy, from Latin America to the Middle East. But it is still a bold move as Obama’s hot wars tally up and critical comparisons to Bush piling on in an election season.

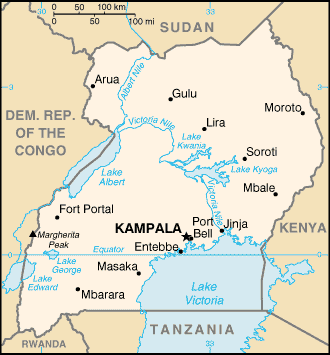

Sending in troops, even in small numbers, in that region has had disastrous effects in the past (Black Hawk Down, years of consequent strife and suffering in Somalia, etc.). The operation already seems more expansive than the small number of troops would suggest, with Obama planning to spread the presence of the commandos to surrounding areas in South Sudan, the Central African Republic and the Democratic Republic of the Congo – some of the most bloody and dangerous places in the world.

The potential for calamitous consequences resulting from yet another war of choice is, to say the least, very high. And for the years ahead, the region is proximate enough to the Arab world that the potential for blowback is at least as likely.